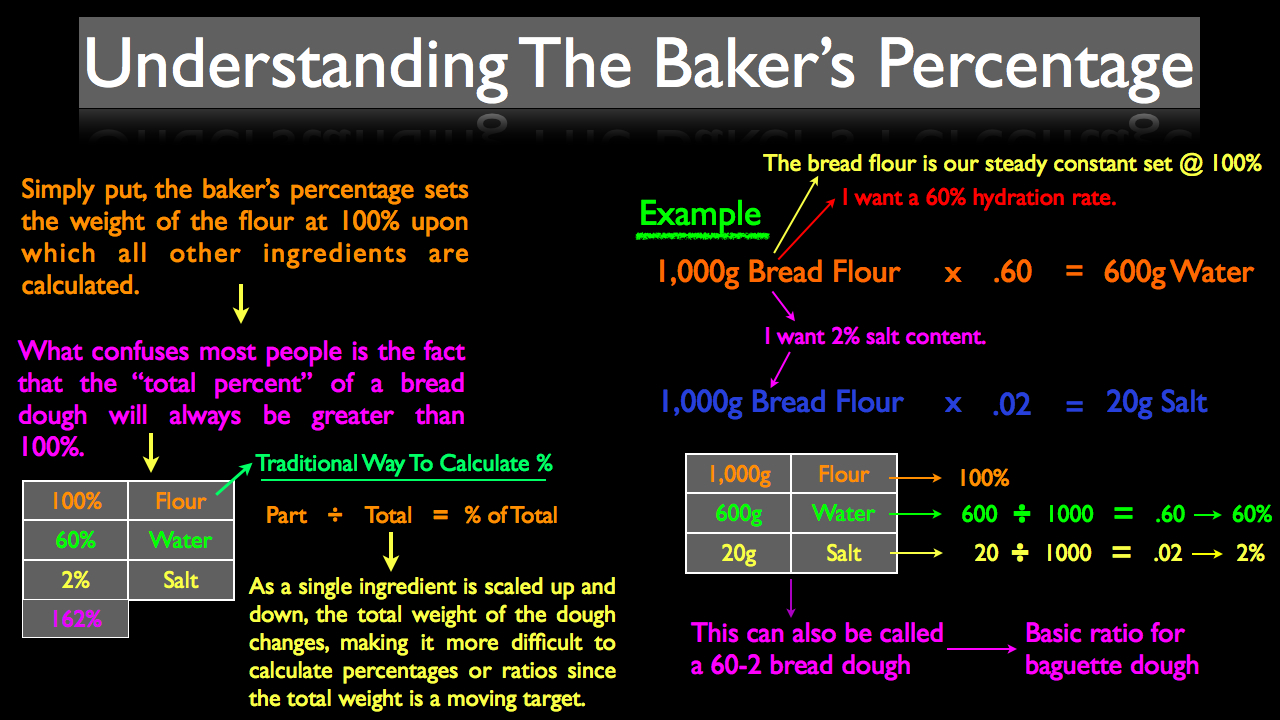

The baker's percentage is an important concept for all cooks to understand, whether or not they actually bake bread.

When you start viewing recipes through the lens of the baker's percentage, you'll start recognizing ratios and patters that you didn't see before. These ratios can later be used to write new test recipes or trouble shoot a recipe that's giving you problems.

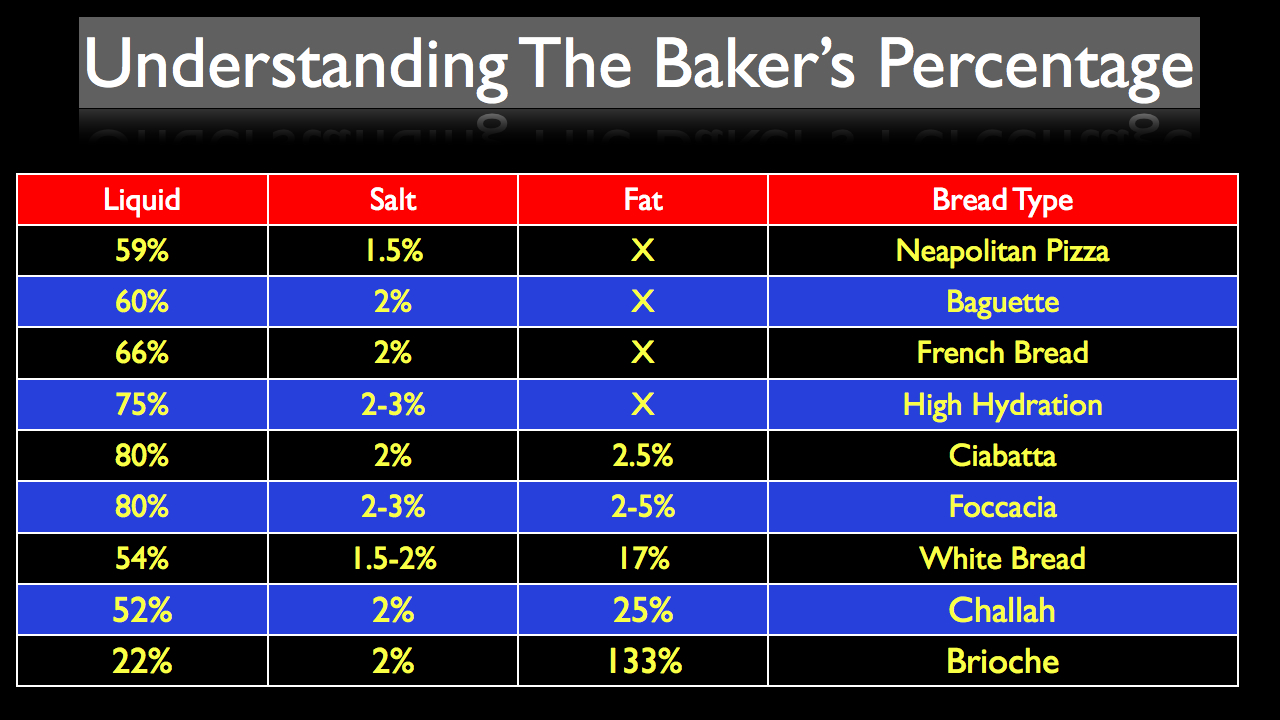

Below is a chart that illustrates traditional ratios for common types of bread dough.

Related Resources

There are 33 Comments

That's why I love Modernist

That's why I love Modernist Cuisine; it's so much easier for professionals to understand recipes in that context. Most kitches that I've worked, and my own personael prefference, is to keep trak of recipes by their weighted ratio, with the main ingredient always set at 100%. It will always give you a better perspective and understanding on the recipes you make or create.

We will eventually tackle the

We will eventually tackle the Sous Vide topic full force in an upcoming video series. This website is still in it's "foundational stage" though, with some more basics to cover before we get into the advanced topics.

I understand your point about Thomas Keller's "Under Pressure," but I would recommend that you try and get use to doing at least some of your more intricate recipes by weight, prefferably grams. It really is the only way to be consistent and 100% accurate. Surprisingly too, you'll find that once you get use to it, executing a recipe that is measured in grams is faster and more efficient then measuring by volume. It just take a little while to get use to.

A couple of things; You

A couple of things;

You should never be measuring anything in volume when working with modern techniques and hydrocolloids. Everything should be weighed out on a digital scale and always in grams. Grams are necessary because there are quite a few calculations based upon percentages and ratios that are used in recipes employing hydrocolloids, with even 1/100th of a gram making a big difference in your outcome.

Generally speaking, when using the standard spherification technique (alginate base dropped into calcium chloride bath), you will add 1% by weight of sodium alginate to your water based flavor and 1% of calcium chloride by weight to your setting bath.

Any time you add sugar to your alginate solution (or flavor base), it will raise the viscosity. Sometimes this is negligible, but in larger amounts, you need to adjust the consistency of your chloride bath to match that of your alginate solution. This adjustment of viscosity is usually using Xanthan Gum, commonly by trial and error.

Also, the best way to hydrate any hydrocolloid is by shearing power, not by boiling (although some ALSO require boiling after shearing, like Agar Agar or Methylcellulose). With alginate, usually just hitting the mixture with an immersion blender for about 60 seconds and then straining through a chinois will do the trick.

Let me know if you have any more questions.

The fats can really be

The fats can really be anything that you want, depending on the desired flavor and texture of the finished product. For example, brioche uses a lot of egg yolks and melted butter to give it a rich flavor and texture. But when making flaky bread products like biscuits, croissants, pie crust, etc, it's important to use cold chunks of butter or other fat.

Common fats used in enriched doughs are butter, cream, whole milk, lard, shortening, eggs, egg yolks, oils (olive, nuts, seeds) and to a lesser extent animal fats like beef suet and duck fat.

Sourdough Starter Flour Percentage

Can you say something about what's a typical percentage for starter flour to total flour in sourdough bread?

For example using 100% starter (equal weights flour and water), I use 50% water, 50% starter, 2% salt. This results in a starter flour to total flour percentage of 20% - is this typical, high, or low?

It depends how quickly you

It depends how quickly you want your dough to rise and the desired, finished flavor. In general terms, the smaller amount of starter used, the longer it will take a dough to rise, but the more flavor it will have in the end. A common starting point is usually around 1/3 of the total dough being made up by the starter.

OK thanks. For 100% starter

OK thanks. For 100% starter and 60% hydration, using 1/3 starter to total dough weight would result in a starter flour to total flour percentage of 27%.

You have to remember that a

You have to remember that a poolish starter is made up 50% water and 50% flour. So if using 500g of poolish, you would calculate it as 250g water and 250g flour.

So your calculation will look like this:

- 750g Flour (500g + 250g flour Poolish)

- 525g Water (275g + 250g water from poolish)

- 525g Water ÷ 750g = .7 or 70% hydration

Hope this helps.

The reasons why you dump the

The reasons why you dump the starter is to feed it fresh and keep it healthy. Don't think of it as "killing" your starter, think of it as necessary process to keep your starter healthy and happy.

As far as just adding flour to the starter, you won't have good luck with that because the environment will be extremely acidic which will weaken the gluten strands in your bread. These weak gluten strands will give you a flat loaf of bread, like in you previous picture. Dumping most of the starter the night before and feeding will give you a "young," fresh starter that will be active and healthy the next morning.

@ Gendari, Yes, it is

@ Gendari,

- Yes, it is possible to make Challah with a sourdough starter. Remove half of the flour from the recipe, mix with the same amount of liquid (subtracting that amount from the recipe), and inoculate with 50g sourdough starter. Let preferment overnight, and then add the rest of the ingredients the following day. Remember, since wild yeast is less vigorous then commercial, you're bulk fermentation and proofing stages will be longer.

- Liquid milk, because it's mostly water, is considered a liquid, versus vegetable oil would be considered a fat since it is pure fat, and will have an effect on the crumb of your bread.

@ SharpKnife,

For ease of measurement, I would classify cream as a liquid, but take into consideration that you'll need less fat in your formulation, if any at all. With that said, it's pretty rare to see heavy cream in a bread recipe. Usually rich dough are made up of milk (even whole milk is mostly water, with about 10% fat), butter and eggs.

Hi Joann, When using liquids

Hi Joann,

When using liquids that contain fat (like milk), treat them as a liquid percent (add them to your hydration ratio). Because they're not pure fat, the fat content contained in the dairy won't have a massive effect on the final out come.

Remember too that when adding milk to a dough, you first need to bring it to a simmer (scald), let cool, and then add. The whey protein found in milk can weaken a dough's gluten structure. Scalding the milk first essentially deactivates the weigh protein, allowing you dough to rise better.

Let me know if you have any more questions, and welcome to Stella Culinary!

Hey Wartface, welcome to

Hey Wartface, welcome to Stella Culinary. I'm glad you found us.

For paragraph formatting, we use a WYSIWYG editor that's Java based. So check to see that you have Java installed and enabled in your web browser. That should fix that.

Now, to answer your questions:

I understand why you left out the yeast/levin from the chart. However when it comes to active dry yeast would it be safe to say .014% of the flour weight would be a normal amount to use in my recipes?

So based on your salt percentage that you quote in your formula, which is really 1.8% instead of .0018%, I'm not sure if you have the decimal in the wrong place here as well. To get a 2 hour bulk fermentation and 1 hour proof, you usually need about 7g of yeast per 1000g of flour, or 0.7%. 1.4% would be 14g of yeast which would be too much for most formulations, and 0.014% would be 1.4g of yeast (per thousand grams flour), which would work, but give you a very slow rise.

Would you say that my 100% hydration starter should be 40% of the flour weight for my sourdough cooks.

Whatever works for you is fine. I usually stick to about 1/3rd of my total flour weight coming from my starter. This gives me a 2-4 hour bulk fermentation and a 1-3 hour proof. The big difference in time is based upon your environment, specifically how hot your room temperature is. Less starter will give you a slower rise and more complexity. More starter, if it's been sitting too long especially, could yield less oven spring and a denser loaf, since the acid built up in the starter will weaken the gluten strands. For more information on the ratios I use, check out this video here: http://stellaculinary.com/how-to-convert-any-bread-recipe-to-sourdough

Do you have a critic of my sourdough recipe? Is there anything I can do to improve it?

Without knowing specifically what you want to accomplish, it's hard to say. There's lots of different approaches to using a sourdough starter, all with different outcomes. If you listen to our sourdough bread podcasts, specifically episodes 21 and 22, you'll hear me talk about lots of different options for building complexity, creating a more sour loaf, creating a more floral, less sour loaf, etc.

with the list of the different breads and the percentages of ingredients, do you have an expanded list that shows other breads and what their percentages are?

I don't have an expanded list. The list at the end of the video was just something I did to put the baker's percentage into perspective. However, I'm not opposed to making a larger info-graphic. Is there anything in particular you'd like to see?

The higher hydration rate

The higher hydration rate will give you a more open, airy crumb. If you really want an open irregular crumb after raising to 70% hydration, you can also incorporate an autolys step (minimum 30 minutes) and stretch and folds.

Check out this loaf that community member Dave just posted. The open, airy crumb is a mixture of higher hydration, autolyse, and stretch and folds: http://stellaculinary.com/forum/all-things-bread/sourdough/rosemary-and-...

In contrast, the lower your hydration and the more you work the dough, the tighter the crumb will be, with smaller, more even air pockets.

That's a beautiful looking

That's a beautiful looking loaf of bread.

If you increase the hydration, you'll get a bit of a more open crumb, but that doesn't necessarily mean it will be a better loaf of bread.

But the more you play, the more you learn. I think raising the hydration bit would be a fun experiment, after which, you can decide what you like best.

Also, if you start incorporating whole wheat or rye flour, you'll naturally want to raise you hydration since higher protein flours will absorb more moisture.